The Truth Behind “Adversity” and What it Means for Irvine Students

September 17, 2019

The debate over how much a student’s background should influence college admissions is not a new one. In recent years, the link between background and admissions has been brought to the forefront of public interest and news, as seen with the 2014 Harvard lawsuit, in which Harvard was accused of discriminating against Asian-American applicants, and the recent scandals of wealthy families buying their children’s admissions into elite universities.

As of last May, this decades-old debate resurfaced with a new life as the College Board announced the expansion of the ever-controversial “adversity index.”

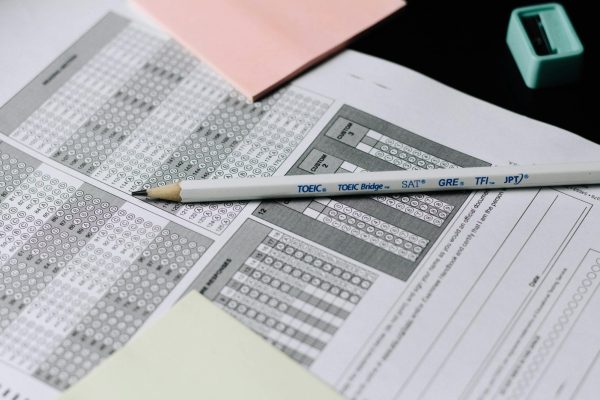

According to the New York Times, this index was a number from 1 to 100 that scored your inherent advantages or disadvantages, considering factors such as the crime and poverty rate of a student’s neighborhood and the quality of education at their high school. Interestingly enough, it did not consider a student’s race – a stark contrast from institutions like quota systems and affirmative action.

This number was sent with a student’s SAT score to colleges, but the student was never allowed to see it. The reasoning behind the implementation of such a tool is solid: certain students simply have access to more – more wealth, more resources, more opportunities – and such students consistently outperform those with less on the SAT.

However, if one takes a moment to remove the rose-colored lenses, it should not take too long to see the glaring cracks in logic.

The adversity score was met, understandably, with massive pushback. While its intent was to reinforce the idea that a student cannot be defined by a mere number (their SAT score), the index actually did just that: assigning a student a single numerical value that was meant to accurately encompass and evaluate the complex circumstances that have shaped their lives.

For many, the adversity index further felt like an attack on meritocracy and an admission that the SAT is a flawed scale for comparing students (Forbes).

Overall, implementing the adversity index to combat the deep-rooted, institutionalized disparity that exists between communities was like slapping a Band-Aid on a deep wound – a superficial and ineffectual “solution” that only served to obscure the core of the issue, allowing it to fester and spread beneath the surface.

Recently, the overwhelming criticism of the adversity index led the College Board to release Landscape, an objectively improved version of the original idea. Rather than assigning a single numerical score that only colleges can view, Landscape offers detailed information about a student’s high school, neighborhood, and socio-economic situation, all of which is transparent to students and parents (Forbes). Unlike the half-baked adversity index, Landscape has the capacity to give colleges a truly holistic view of a student’s circumstances and, more significantly, their resourcefulness in the face of such circumstances.

For students living in Irvine – one of the safest, wealthiest, and best-educated communities in the nation – it can be hard to fairly evaluate such a measure. Many here stand firmly against any sort of adversity report, arguing that students born into privilege still have to work hard to get good scores.

However, while this is certainly true, this argument is often made from the standpoint of a student who has received a commendable education their entire life, has access to a variety of exceptional resources and test prep classes, and does not have to worry about matters like where their next meal is coming from or whether it is safe to walk to school.

The fact is, this is not the case for most aspiring college attendees. According to the National Center for Children in Poverty, a whopping 43% of children in the United States live in low-income families, and living in poverty has been found to be the single greatest threat to a child’s education and wellbeing.

What we need to understand is that Landscape and other measures like it are not meant to automatically give admission preference to “poor minority kids” over privileged students like us, as so many scornfully assume.

Rather, such measures are meant to help level the playing field, albeit to a small degree, for the sake of those who have always found themselves on the bottom of the hill.

The primary purpose of a standardized test has always been to provide a blunt measuring tool to mitigate the inherent inequalities that hinder fair comparison of students, such as the variable difficulty of high schools. However, if standardized tests are actually doing the opposite (uplifting the “lucky ones” while further alienating the “less fortunate”), then why shouldn’t the College Board take action to lessen this divide?

By giving fair opportunity to students on the other end, Landscape has the potential to help break the almost inescapable cycle of disadvantage in which hundreds of communities are trapped.