Barbie is the Bane of Positive Body Image: A response to “Barbie’s not the problem, you are” by Lilia Abecassis. View the original article at https://uhsswordandshield.com/2014/05/20/barbies-not-the-problem-you-are/.

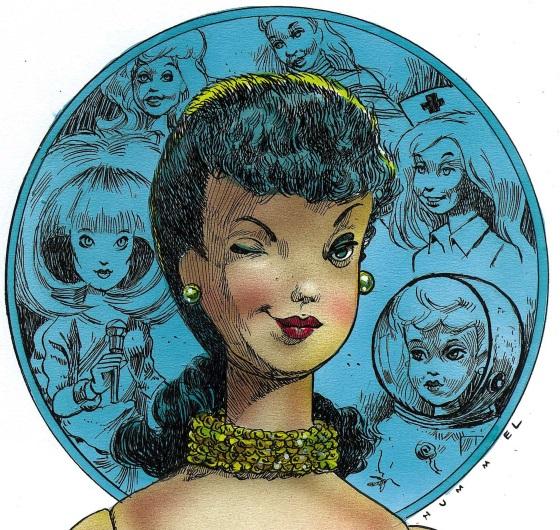

Barbie dolls: we all know what they are; after all, they have become a societal fixture in the United States since Barbie’s inception by Mattel, Inc. in March 1959. They are so embedded in American culture that only one percent of girls in this country have never owned one before. According to the South Shore Eating Disorders Collaborative, the average American girl receives her first Barbie at the ripe young age of three and collects about seven dolls in total by the time she turns twelve. They are even a staple internationally: every second two Barbies are sold across the world.

With such a long-term and domineering presence in international culture, it is only logical to conclude that Barbies greatly affect children’s image expectations, especially since the target age range for Barbies is from age three to twelve, a time when children are highly impressible as they are experiencing intensive cognitive development. Now, Barbie’s extensive influence on children is not necessarily harmful. These dolls can be considered inspirational–or at the very least, positive–role models for young girls since Barbies can have diverse occupations, such as Lawyer Barbie, Astronaut Barbie, Race Car Barbie, etc. Many of the various careers Barbies are portrayed in are actually professions usually dominated by males, encouraging girls to challenge gender roles when it comes to career paths.

However, when it comes to children’s perceptions of body image, and therefore their self-esteem, Barbie’s widespread impact is detrimental. According to the Adolescent Nutrition Services at the University of Minnesota, Barbie would be seven feet, two inches tall if she were a real female. She would also have a chest of 40 inches, a waist of 22 inches, a neck circumference of 12 inches and a neck length of 6.2 inches. Her neck would be too thin to support her head, her waist would be too small to accommodate her body’s vital organs and her body proportions would be so skewed that she would have to walk on all fours to support her weight. Barbie’s body is highly unrealistic, almost laughably so.

What does that suggest about body image to children, adolescents and even adults, who have grown up constantly interacting with Barbie dolls, in a society that continuously forces them to compare their bodies to others’? It hurts their self-esteem by relentlessly reminding them their bodies are not the “right” size or proportion. It is especially damaging for young children who begin playing with Barbies at age three. In terms of psychologist Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development, these children are in the preoperational stage where they become adept at using symbols to represent other objects. To them, a Barbie easily becomes a symbol, and that is where Barbie’s unrealistic proportions become problematic. The Barbie comes to symbolize “woman”–and maybe also the occupation it portrays (i.e. a Lawyer Barbie would symbolize “lawyer”)–which means the Barbie becomes the default image of “woman” to the child. As the child grows up, she will repeatedly question why her own body does not fit the default, yet completely unrealistic, image of “woman” she had believed in since her early childhood. In fact, according to the National Eating Disorders Association, 69% of American elementary school girls say pictures in magazines influence their perception of ideal body image and 47% say that these magazine pictures make them want to lose weight. Pictures in magazines portray likenesses of women, and what are Barbies but tangible, three-dimensional likenesses of women the girls see in their homes every day?

If those statistics are not convincing enough, psychology professors Helga Dittmar, Suzanne Ive and Emma Halliwell conducted an experiment in the United Kingdom in 2006 called “Does Barbie Make Girls Want to Be Thin? The Effect of Experimental Exposure to Images of Dolls on the Body Image of 5- to 8-Year-Old Girls.” In their experiment, the professors exposed 162 girls from ages five to eight to images of either Barbie dolls, Emme dolls (which are considered a more realistic U.S. size 16) or no dolls (as the control group) and assessed the effects on each girl’s body image. At the end of the experiment, the professors concluded that girls exposed to Barbie doll images had “lower self-esteem and a greater desire for a thinner body shape than in the other exposed conditions.” They also found that the images made less of a negative impact on the oldest girls in the group; however, if they had been previously exposed to Barbies, the girls still idolized a grossly thin body which increased their risk of developing eating disorders.

Although the 2006 study proves a correlation between Barbie and unhealthy body images, there is always an exception to the rule. Barbies do not negatively affect every single child they come in contact with; however in those cases, social activist and critical theorist Bell Hook’s idea of “Dirty Water” suggests that the child typically lives in a comfortable home environment where parents or other guardian figures can encourage a healthy body ideal and boost the child’s self-esteem, an environment which typically manifests itself in families of Caucasian descent with a relatively high socioeconomic status, since minority groups fall subject to acculturation and lower class Caucasians are preoccupied with more pressing economic needs.

For every person who seems to escape the curse of Barbie culture, another person is extremely affected by it. For example, body dysmorphic disorder, a disease in which a person obsesses over one part of their body they do not like, drove reality T.V. star Heidi Montag to go through ten plastic surgeries in 2010 to achieve a “Barbie-Doll body.”

Barbie may not be the sole and direct cause of distorted body images, low self-esteem or eating disorders, but research has proven time and time again that she is part of the problem. Although she may not have largely impacted body image in the fifties, sixties and seventies, her wide-reaching influence now is undeniable. As a true fixture in contemporary international culture, Barbie flaunts her unrealistic proportions across the globe, a subtle subliminal message to every girl to strive for a thinner figure.

By CHRISTINE SMET

Staff Writer

marieechristine • May 20, 2014 at 3:59 am

Reblogged this on Always Expressive and commented:

No one should be blamed for their self esteem issues.