By ARNI DAROY & PETER THOMAS

Executive Editor and Copy Editor

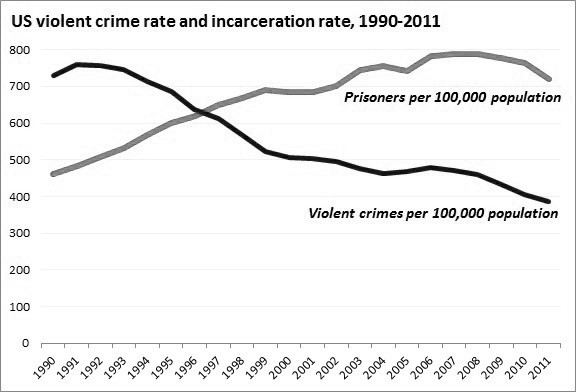

There are many problems with the prison system in the U.S. One is the number of people in the incarceration system alone. According to the Centre on Prison Studies at the University of Essex in the UK, the largest publication of studies on the global prison population, the U.S. has about 4.4% of the world’s population, yet about 22% of the world’s prisoners/incarcerated people.

According to these numbers and the Population Reference Bureau, the U.S. has the highest incarceration rate in the world at about five times the world average – with one out of every 100 adults in the U.S. in jail.

The American prison system often affects individuals and communities unfairly. David Gist, California and Arizona regional organizer for Bread for the World, an organization that protests mass incarceration, states that “mass incarceration is a big issue because current policies and practices discriminate against people of color, particularly African Americans and Latinos/as.” Often, African Americans in particular are integrated into the vicious cycle of incarceration via the “war on drugs.”

Though black people comprise 13% percent of the U.S. population, they account for 30% of those arrested for drug law violations and nearly 40% of those incarcerated in state or federal prisons for such infractions, according to drugpolicy.org. In order to incur a mandatory minimum sentence for a drug-based offense, one must be in possession of either 500 grams of refined cocaine or just 28 grams of crack cocaine, according to Vox. Crack cocaine is significantly cheaper than refined cocaine, and thus more common in black and ethnic communities.

In conjunction with unequal mandatory minimum sentencing thresholds, this disparity results in a disproportionate number of African Americans and Latino/as in the prison system, enduring lengthy five-year prison terms sometimes for just being in possession of illicit drugs. In fact, one in three black male babies born today will end up in jail, according to The Washington Post. The carceral state therefore promotes racial discrimination in American society and has increased the social and economic pressures faced by African-American families.

Even if incarceration was fair, however, the system is still flawed as it focuses more on punishment than on rehabilitation and correction. According to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, nearly 50% of the federal prison population consists of people charged with nonviolent drug offenses, while only 8% are charged with violent crimes. Victimless crimes are responsible for 86% of convictions in the federal prison population, meaning the majority of people in prisons are not there for violent crimes, let alone crimes like homicide or murder.

Proponents of mass incarceration have generated a sense of fear in our minds: without prisons, society will become overrun with murderers, druggies, rapists and other criminals. Their concerns are not entirely unreasonable — there are those who commit atrocious acts and those who break the law, and those people should be punished to the fullest extent of the law.

But when more than half of state prisoners are serving time for nonviolent crimes, and when 1/3 of the people receiving mandatory minimum sentences in prison have little or no criminal record, mass incarceration has surpassed enforcing justice and has begun to abuse it according to the New York Times and the U.S. Sentencing Commission Report to Congress.

Not only does the U.S. enforce mandatory minimums on prison sentences, but U.S. prisons also violate international standards with inhumane practices, including solitary confinement and the death penalty. The point of prisons is to punish people for crimes, but more importantly, prisons should prevent crime from happening again and deter others from breaking the law.

In terms of rehabilitation and correction, one of the most fundamental concepts in criminal justice is the ability of prisoners to be able to contribute to society after serving their sentences. Many prisoners from lower socioeconomic classes return to disparate conditions only to find their families in shambles, jobs lost, and homes foreclosed.

A report by the National Academy of Sciences described how the lack of rehabilitative institutions and facilities available creates a vicious and “highly distinct political and legal universe for a large segments of the U.S. population.” While the federal prison system, according to Families Against Mandatory Minimums, consumes over 25% of the Department of Justice’s budget, the vast majority of that money is spent not addressing, but perpetuating recidivism.

The recidivism rate in the U.S. is 68% for the first three years, meaning that within three years of release, over two-thirds of prisoners are rearrested. In many of these cases, former prisoners commit petty crimes in order to be arrested, as they cannot have lives outside of prison. These convicts are not only less likely to be hired for jobs, but they are also ineligible for welfare, student loans, public housing and food stamps. These factors lead to more than higher recidivism rates and are also responsible for higher levels of homelessness and suicide among former prisoners.

Focusing on punishment is not simply ineffective in preventing crime; it is overwhelmingly expensive. In the last 20 years, the amount of money spent on prisons has increased by 570%, and, according to CNN Money, the amount the government spends per prisoner per year in California alone is around $45,000. “Every dollar our nation spends on incarceration is a dollar it can’t spend on either prevention of crime, public safety or support for hungry people,” said Gist.

Ultimately, those funds should be redirected towards rehabilitation programs such as mental counseling, post-prison employment and health care. Policymakers in the federal government and several states, including California, are not apathetic towards mass incarceration. According to Kathleen Lewis, the criminal supervising judge for the San Diego Superior Court, “the tide is changing and prison overcrowding is not the same as it was ten or fifteen years ago.”

Lewis described how ballot measures in California, such as Proposition 47, which made a number of non-serious and non-violent crimes, including shoplifting and forgery, misdemeanors as opposed to felonies, have incentivized fewer punitive measures in the justice system.

In Congress, legislation proposed earlier this year, such as the REDEEM and Smarter Sentencing Acts, aimed to promote prison reform on a national scale. More recently, prospective presidential candidate Hillary Clinton announced her intentions to end the era of mass incarceration, according to the Huffington Post.

All the same, policies and promises do not address the problem of rehabilitation. “There is nobody really helping [former prisoners] to improve their lives: there aren’t very many organizations that focus on providing housing, jobs, child care and psychological and medical resources,” Lewis said. And even more difficult to address is the resentment mass incarceration has instilled in communities it has affected adversely. According to The Atlantic, contemporary American politicians that aim to discard the failed criminal-justice system they have inherited must reckon with the history of repression it created.

For too long, mass incarceration has been treated as a panacea to America’s criminal problems, used as the medicine to cure all ills. But it is abundantly clear that instead of ameliorating the sick body of American society, mass incarceration has infected it anew with such pathogens as inequality and discrimination. So long as the current prison system focuses on punishing prisoners, it does not deter crime: it repeats it.

Combined with high incarceration and recidivism rates, the prison system, despite all the money that has gone into it, has proven to be ineffective. Punishment, while a part of the process, should not be the focus of prisons, and until the US prison system changes to include more programs to correct and rehabilitate prisoners, it will not deter crime. By changing prison policy to center more on rehabilitation, prisoners and society as a whole stand to benefit. Mass incarceration may be a tragic aspect of the present, but it does not have to be one of the future.