By AKANKSHA SAH

Opinion Editor

In our society, we strive so hard to attain that ever shifting, ever morphing target of equality – we need equality for races, sexes, sexual orientations, socioeconomic classes – the list goes on. In our efforts to reach that perfect society, though, we often create for ourselves new imperfections.

Not too long ago, married couples needed one of a select number of legal reasons for a divorce: domestic violence, though frowned upon in most cases, was not one among them.

Married women had essentially no rights, even to their own children; according to Dailymail.co.uk, in Victorian England, if a married woman who left her house seeking refuge from her husband returned for her children, it was well within her husband’s rights to bar her from reentrance and to lock the children in and keep them from her, no questions asked.

The United States, though an independent country, had its own foundations for marriage policies planted firmly in that same conservative, male-centered world.

Women, although eventually legally allowed to file for divorce on the basis of abuse, had a difficult time actually proving their case in most instances.

According to the National Paralegal College, it was not until the 1970s that “no-fault” divorces, in which neither side had to prove any misconduct on the part of the other, became legal in the United States, and only then were women able to leave an abusive marriage without facing serious stress and questioning from legal procedures.

As our society has become more and more progressive, we have started to stick up for the little guy; we see a situation and figure out how we can make a hero out of the underdog. In keeping with this policy, we encourage women in abusive relationships to leave, and we hold up as heroes rape victims who report.

This progress is significant – we have long been in want of such reform; but what are the unseen costs of this shift in attitude? Can there even be a downside to so positive a change?

Unfortunately, there is. Somehow, in our mission to give one group its rights, we have unintentionally left another helpless.

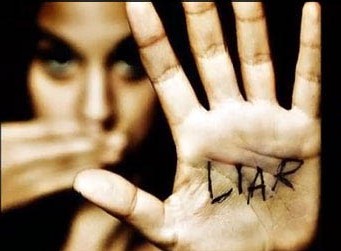

With the current system, all it takes is one accusation from a woman against a man for that man’s entire career, reputation and life to be unalterably damaged.

Of course, this is acceptable in cases in which the man is guilty as charged, but what about those in which the men are innocent? What about those men who have actually done nothing wrong, who are simply the unfortunate victims of a passionate whim of an angry woman?

According to Domestic-violence-law.com, in our courts, if a case involves a woman’s word against a man’s, the woman’s version of events is almost always valued more. If a man is accused of abuse – physical, sexual and sometimes even emotional, even in the absence of definitive evidence, he is almost always found guilty.

In a discussion on Reddit, one man, a former calculus teacher, spoke of his experience with a female student who threatened to accuse him of attempted rape. He said of the incident:

“Fortunately for me, the headmaster was just around the corner and witnessed the whole thing. However, I went on to resign at the end of the year. I don’t need that kind of worry in my life. In the end, had the headmaster not been nearby, and had it [come] down to my word against a student’s, who knows what would have happen[ed].”

Clearly, a system in which an innocent man is forced to resign because of the threat of a false accusation is flawed.

The solutions that people in such cases have been forced to come up with, too, are less than ideal. Male teachers must be conscious of who is in the room with them at all times, even going so far as to impose restrictions upon themselves in simple, day to day interactions. In a piece he submitted to Education Week, teacher and author José Vilson said, “I do have to make sure that, when I speak to my girls, it’s in an open-door setting or amongst a larger group of students.”

It is unfortunate that these good people are forced to look out for situations that could lead to false accusations in a manner that almost makes libel seem normal.

The way we look at false accusations is similar to the way that we look at actual rape cases: we preach safe behaviors to potential victims in a system that says “don’t get raped” rather than “don’t rape.”

Why is it always the victim’s responsibility? Why are people, including teachers – the people we trust to take care of and guide our children – forced to sacrifice their roles as mentors in order to ensure their own safety?

The skewed way in which we look at women and men regarding abuse is clear even just in regular social situations.

When we see a girl walking down the street with a black eye, we think abuse. When we see a guy walking down the street with a black eye, we think fight.

If that girl were walking with her boyfriend, he would get dirty looks; if that man were walking with his girlfriend, she wouldn’t get a second glance.

How is it acceptable for people to view situations in such a skewed manner? Why are men treated as guilty until proven innocent?

It is indeed important to think in terms of the worst-case-scenario and to ask and make sure that someone who is hurt is, in fact, safe. I am not saying that we should assume that injured women are not being abused – just that it is equally important to consider abuse in a man’s case as it is in a woman’s.

Statistics do show that women are more likely than men to be victims of abuse, but at the same time, wouldn’t it be awful to be that anomaly – an abused man – in a society in which no one cares for or even considers your plight?

The legal system for abuse cases is the way it is so that actual victims do not have to be afraid to speak out, safe in the confidence that they will be believed. I am not trying to undermine this cause; personally, I have seen first-hand the effects, both physical and emotional, of domestic violence, and I support abuse victims with all my heart.

At the same time, though, I see that a door for others to be victimized has unintentionally been opened in the process.

How can we reconcile the issues of believing victims and defending innocent people?

Honestly, it is a difficult question to answer. I don’t know the answer, and I don’t profess to.

But I do know that we need to stop ignoring the problem – we need to accept that it exists and seek a solution, and we must spread awareness until we have found one.