By MATTHEW CHONG

Staff Writer

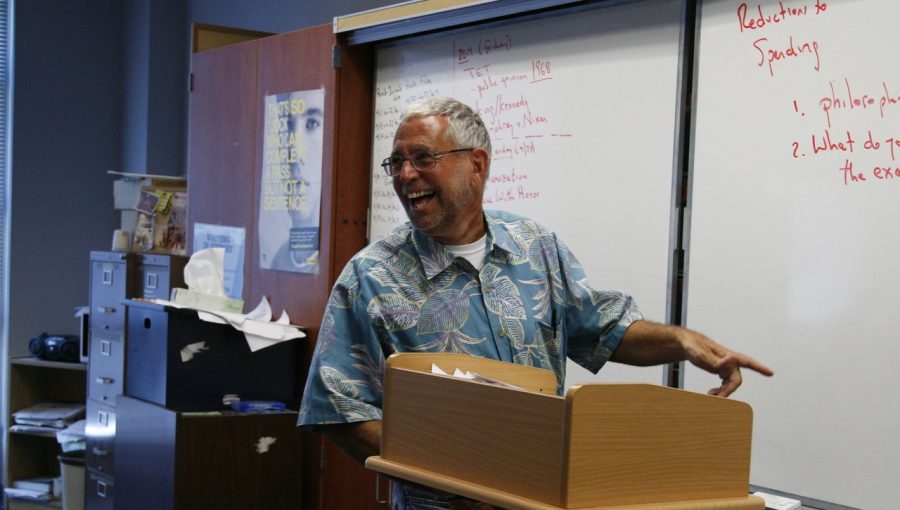

At first glance, the classroom of Mr. David Mallis (Social Science Dept.) may seem unimpressive. The walls are bare, save for a few posters dealing with United States history. Even the whiteboards are plain; they are routinely wiped clean after class ends. From time to time, a familiar song can be heard on a CD player. Simon and Garfunkel. Creedence Clearwater Revival. If the song in question is from the 1960s, the history teacher probably has it in CD form on one of his shelves. Mallis himself may appear unassuming as well, dressed in his customary Hawaiian shirt, jeans and running shoes. However, he may very well be the only teacher on campus who has taught history and taken part in it as well.

As a teenager in the 1960s, Mallis was on the front lines of social change, doing his part in the fight for equality. After living overseas for the first ten years of his life, Mallis and his family returned to the United States and settled down in Bloomington, Indiana. While living in Bloomington, he played an active role in various organizations, one of which was Project Head Start.

As one of President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs, Project Head Start was intended to provide child care and other services to low-income families. While working for the government program, Mallis taught and cared for the children of these families. (A few years later, he graduated from Indiana University with a Master’s degree in Early Childhood Education.)

Mallis’ activism extended to other issues besides poverty. In the late 1960s, he joined the Civil Rights movement as a member of the Black Panther Party. Founded in the city of Oakland by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, the Panthers were considered a militant group by the American public. “I felt that their point of view as far as immediacy was far more correct than Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s policy of passive disobedience,” he said. “If I was black, I would not want my son’s son’s sons to have a better experience,” he said. “I would want that experience to start with me.”

Though he did not take part in any marches, Mallis still worked within the political party. In 1969, the Black Panthers initiated a number of social programs, creating food banks, health clinics and other services for local African American communities. “[The Black Panthers] had me working with shut-ins in Bloomington. I went around to people’s houses and if they couldn’t get out, I’d get their medicine or get their shopping done and bring those items back to them. The media in Southern Indiana was so anti-Panther, and we had tried to shine a better light on the organization by providing these services.”

With the passing of the Tonkin Gulf resolution in 1964, the conflict in Vietnam began to escalate, and Mallis was soon drafted into the war. However, he was given a 4-F designation, which granted him a medical deferment. But like many young people in 1960s America, he was disgruntled with the country’s involvement in the conflict. “I could never understand the war, and I couldn’t see the grotesque fear that was inherent when you heard the word ‘communism,’” he said. “I still don’t understand how people dismiss things like socialism without even understanding what the word means, especially when two of the basic tenets of our country, Social Security and Medicare, are both socialist programs.”

In response to the Vietnam War, and other issues as well, Mallis joined the local chapter of Students for a Democratic Society, or SDS for short. “The SDS had various kinds of things that they were in favor of,” he said. “A lot of it had to do with free speech, a lot of it had to do with getting the heck out of Vietnam, a lot of it had to do with people living better, more idealistic lives.”

As a member of the SDS, Mallis participated in a number of protests, some of which ended with his arrest. “During one march at Indiana University, we shut down the school’s main building by chaining ourselves to the doors, and so we all got arrested,” he said. “It was a more purposeful time. Everybody had an opinion, and you were either for or against the issue in question. Nobody ever said ‘I don’t know,’ ‘I don’t care,’ or ‘I don’t understand.’ Everybody was hell-bent on change.”

Besides social causes, Mallis had (and still has) a keen interest in music. When he was seventeen years old, he was able to attend the Woodstock Music and Art Fair, which was held over four days from August 15-18, 1969. “A friend of mine and I had heard about a concert being held at Woodstock, New York, and we bought tickets which were very inexpensive,” he said. “My mother let me borrow her car, which was a tank, an Oldsmobile 98. There were half a million people at the festival, and I guarantee you, I was the only person there with an Oldsmobile 98.” Mallis remained at the festival for its entirety with the opportunity to see Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and Bob Dylan perform live onstage.

His most memorable moment at the festival happened on the first day, or rather, in between the first and second days. “In the middle of the night, during a driving rainstorm, Joan Baez sang ‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot’ while the audience was turning on their lighters and lighting candles,” he said.

But of all of the experiences that he had in the 1960s, being a part of the counterculture was the most memorable. Characterized with the words “Sex, Drugs, and Rock n’ Roll,” the counterculture movement represented a major shift in American society.

In the previous decade, American society had arguably been more conservative and homogenized, demanding conformity from each and every one of its citizens. From capitalism to color, the country presented itself as having a uniform set of values.

A change was soon underway, however. Beginning with the Beatniks of the late 1950s, who refused to “keep up with the Joneses,” American youths began to rebel against adults.

With the advent of the 1960s, conservatism had given way to idealism, as represented by the counterculture. “The movement made people more open to what other people thought, although at the time we had our opinions as to who was right or wrong,” Mallis said. “But at least we listened to what other people were saying.” I don’t know if there was a better time in the world, or at least this country, to have been coming into your own in terms of age,” he said. “[Members of the movement] tried to carve out some kind of identity for themselves, one in which we would be respected by the adults running society. In other words, we wanted to be recognized as having opinions that were relevant and needed to be listened to.”

Even in hindsight, Mallis defends his involvement in the movement. “Understand that every single person goes through a transitionary period where they try and experiment with different things. Then they either move on or get stuck in it,” he said. “That’s all just a part of finding out who you are.”

But in spite of the work that he had taken part in, Mallis harbors doubts about the future of the country. In his opinion, the country has taken a turn for the worse. “We seem to go three steps forward, three steps back, then two steps forward. I don’t know if we’re in a position now to be proud of the advancements that have been made since Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, and I have no idea what’s going to move us forward at this point.”

An era of change: a UHS teacher reminisces about life in the 1960’s

April 27, 2016

0

Tags:

Donate to Sword & Shield

$180

$1000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of University High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover