By MILES HUNTLEY-FENNER

Student Contributor

Writer’s Note – This short story takes place in a fictional world with imagined continents, peoples, and cultures that are inspired by, but are not to be confused with those of Earth.

The sleep-deprived men of Alpha Company’s first platoon awoke to the familiar sound of Warrant Officer Rodska’s booming voice, and stood at attention beside the aging frames of their squat, uneven, and dilapidated beds. It was 3:00 AM Wüstern Peninsular Time, which was three time-zones West of their location the prior night, compounding the effects of the poor sleeping arrangements. The men made their beds at Officer Rodska’s command and formed an inspection line at the center of the room. Rodska, whose sleeping arrangements had been no better than those of his men, looked over his company with a harsh grimace and a sharp frown. Within two minutes, he revoked eleven breakfast rations. Before the inspection was complete, Private Strotsky, the Platoon’s “whipping-boy”, was found to have smuggled an imported apple from the mess, which he had hidden among his personal belongings. This gave Rodska today’s excuse to send Strotsky to the dreaded whipping pole, which was almost exclusively reserved for the poor private every morning after inspection. Strotsky, however, cared little about this morning’s abuse, for he was preoccupied with moral misgivings over the atrocities that he and his compatriots were to commit later that day.

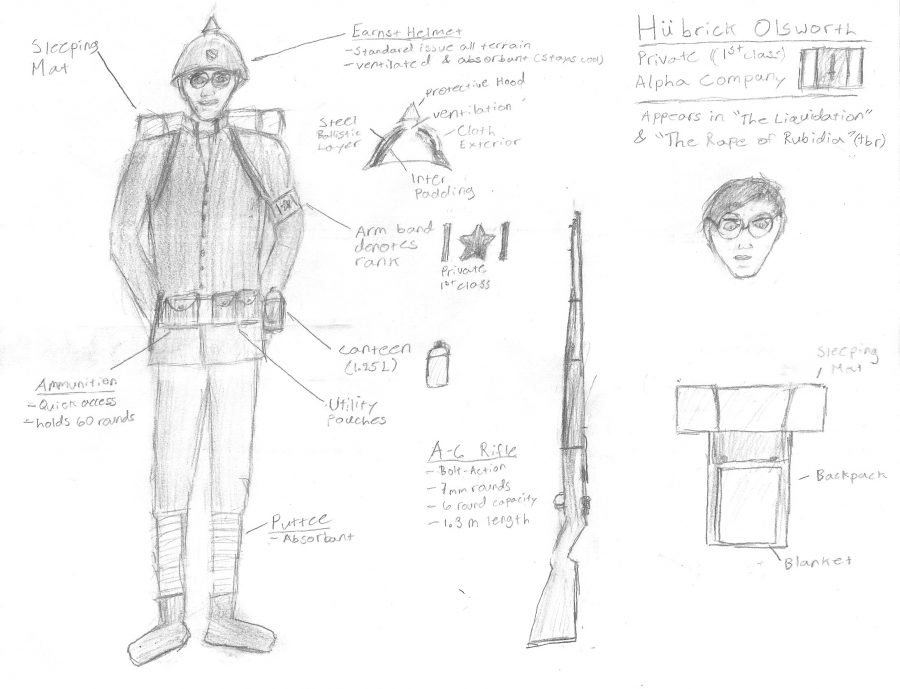

The rest of the men left the barracks and joined their infantry battalion in the mess, where they ate a paltry breakfast of tasteless porridge and stale crackers. Strotsky joined his Company fifteen minutes later, his ravaged back adorned with five new lash-wounds. He sat with his friends, Ingolls and Hubrick, and lamented the revocation of his breakfast ration. His thoughts soon turned to the faces of the men, women, and children who would be massacred and deported that afternoon, and he contemplated whether his friends shared his moral objections. Ingolls had seemed disturbed to him at yesterday’s briefing, which was steeped in racist rhetoric and lacked sympathy for the civilians who were to be systematically murdered and displaced for housing suspected militants. Numerous federally funded race studies had concluded that the Wüsterners were an inferior people. Strotsky, however, believed they could still feel pain and emotion, perhaps not in the same capacity as their Central Pölish neighbors, but certainly to a greater degree than the lower animals they cultivated. Outwardly, Ingolls was as patriotic as any man in the Company. Still, from time to time Strotsky thought he observed a hint of empathy or perhaps even moral objection seeping through. However, Hubrick’s manifest disdain for the inferior races ran deep within his character. He had lost close relatives in the Last Wüstern rebellion, and constantly expressed his satisfaction at retaking the South and “giving those Wüstern bastards what they deserve”.

After breakfast, the men returned to their barracks, dressed, and prepared to depart. They filed through the armory, each collecting their standard-issue reliable, but outdated A6 bolt-action rifle, one hundred rounds of ammunition, and an accompanying bayonet. After filling their canteens, the men assembled in the camp staging area. Their spiked helmets bobbed with laughter as they exchanged jokes and partook in lighthearted conversation. Almost all of the men in Alpha Company, and the entire battalion, carried empty packs in which they hoped to stow away looted valuables from the homes of their future victims. Even Ingolls had a small valuables sack fastened to his utility belt, though it was unclear whether this was of his own accord or due to Hubrick’s coaxing. Strotsky, however, went without any such container. Appropriated valuables officially belonged to the Pölish Government, but the battalion’s Commanding Officer (CO), Lieutenant Colonel Peterson, was to oversee this operation. He was notoriously lenient, and had gained the adoration of his men by granting them constant reprieves from military regulation. His apathy, constant blunders, and frequent disregard for rules had endeared him to some of the men but thwarted his advancement, despite his wealthy upbringing, to which he owed his current position. In fact, with the Emperor’s new fixation on military revitalization and expansion, he was likely to be discharged altogether for his poor quality of service. Peterson understood his predicament, yet, such matters did not trouble him. He was more concerned with maintaining his popularity with the men of the battalion than his superiors.

Peterson approached the staging area with the other COs and addressed his men in a lightly humorous fashion. After dismissing his battalion to board a convoy of military trucks parked around the staging area, he boarded one of several jeeps with the other COs and army interpreters. The convoy departed after the Lieutenant Colonel shot off a round from his offensively loud antique pistol, a family heirloom that he preferred to his standard issue handgun despite its impracticality.

The convoy made its way across the barren landscape, passing the occasional dark skinned, famine-stricken civilian. These became the unfortunate target of insults from the passing soldiers, who jeered racist slurs and shouted what few curses they knew in the southern language. The passing Wüsterners seemed to ignore these verbal assaults, perhaps fearing what would befall them if they retaliated. Hubrick’s contribution was a rock swiftly flung at a passing woman and her three children. The projectile struck her youngest son squarely on his forehead. The boy collapsed, his weak frame incapacitated by the force of the blow. His mother cried out and rushed to the side of her fallen son, where she proceeded to cradle him desperately through a stream of tears as her other children attempted to resuscitate their sibling. The pain of this grief-stricken party was lost on Hubrick, whose celebration at landing “a difficult throw” drowned out the lamentations of the anguished family. This excitement roused Strotsky, who had been sleeping a few seats away from the triumphant Hubrick. After learning the cause of the commotion, Strotsky settled back to resume his slumber, annoyed at being roused, and slightly disturbed at what had happened. The family soon slipped out of view of the convoy, along with the pool of blood that had formed around the fallen boy and his mother.

The convoy proceeded without further incident for several hours before finally arriving at the small town that was to be liquidated, nameless to those who had destroyed so many like it. The Lieutenant Colonel was spurred to action, and at the sound of his whistle, the men took their positions. A perimeter was formed around the still unsuspecting inhabitants of the doomed settlement. The rest of the battalion, segmented by platoon, went from door to door, some groups with interpreters, others without. The presence of the interpreters, many of whom only had a rudimentary understanding of the “inferior Wüstern language” was perfunctory. Force was the universal language that governed the interaction between the oppressors and the oppressed.

Some left their homes quietly, and obeyed their captors’ every command. Other, prouder, occupants left under verbal protest. The proudest occupants refused to leave at all, and were punished accordingly. Those who survived the initial raid, some traumatized at witnessing the violent deaths of their friends and neighbors, were brought in front of the town for processing. Half-dressed mothers with unkempt hair stayed their own tears, and instead tended to their children. Other people were silent, struggling to accept what was happening around them. This group suffered the most abuse, as the soldiers beat, shoved, and led their dazed captives to join the others in the assembly area. A small but vocal minority of young men continued to protest their treatment, but were eventually beaten into submissive silence. Once gathered, the civilians went through the first wave of processing.

A group of soldiers sorted the disorderly group, directing men and boys of fighting age to the left, and all others to the right. Strotsky, who was among the sorters, took pity on the Wüsterners, and defined “fighting age” as exclusively as he could without arousing suspicion. Other sorters were much more inclusive. One was even reprimanded for trying to send women to the left, and was replaced.

Once the suspected militants had been separated from their families, they were tied up into eight long rows, each two abreast, and led to a field at the other end of the town. The doomed men carried themselves proudly and wore indignant expressions, having accepted their fate. They offered no physical resistance as bullets shredded their ranks and pierced their flesh. It was no more than five minutes before the machine guns were silenced by the order to cease-fire. Fifty or so soldiers who had been standing at the wayside fixed their bayonets and spent the next half an hour combing through the mangled, lifeless mass of bodies, killing those who had survived the initial gunfire. Many were repulsed by this task and held handkerchiefs over their faces in a vain attempt to alleviate the stench of human flesh putrefying in the afternoon sun. Others took sadistic pleasure in mutilating the dead and dying, delighting in the death throes of those they murdered and dragging their bayonets through the tangled, lifeless mass with macabre fascination. Confident that they had fulfilled their orders, the band of soldiers left the field and the unburied dead within, cleaned their bayonets and made idle conversation as they returned to the front of the town.

Near the convoy, the surviving townrs were driven into hysteria by the sound of the massacre. Mothers who had concealed their sorrow suddenly wept at the deaths of their husbands, sons, and brothers. Their children, who had been comforted by their mothers’ strength until then, broke down and cried with them. The elderly grieved silently, but no less passionately than the rest. The shrill wailing of the grieving crowd reached the intolerant ears of Officer Rodska, who was losing a game of Tek to a fellow relaxing officer in an empty convoy truck. Rodska shook his head and criticized Lieutenant Colonel Peterson for his thoughtless decision to execute suspected militants before deporting the women and children. His opponent muttered in agreement, and proceeded to take Rodska’s king.

By the time the execution squad returned, the hysterical survivors had been subdued, and the second round of sorting had begun. This time, the elderly and disabled were separated from the women and children, who were loaded onto trucks and driven away. The “viable workers” would join survivors from other towns, some with their male populations intact, at a resettlement center in the east where they would provide forced labor for Northern Corporations and the military-industrial complex. It was in this fact that Strotsky was able to console himself. He convinced himself that these laborers would be given a new life, and though he and those like him had caused them great trauma and hardship, these inferior people were better suited for such a simple and miserable existence than their more sophisticated masters in the North. Strotsky’s mind turned to the famines and war that had caused so much death and suffering in his home country and shattered the pride of an empire. He decided that this forced labor, though perhaps immoral, would put an end to national hunger, revitalize the broken Pölish economy, and strengthen the military for its eventual revenge against the West for the millions of lives lost in the war. Although these thoughts did not relieve his empathy, they justified his actions, giving him the conviction to carry on through the day.

Strotsky and his fellow soldiers then fastened their bayonets and finished off the remaining undesirables. Peterson congratulated his men on their work, and gave them until sundown to pillage the town and supplement their meager rations. Peterson then slipped away, secluding himself in a deserted house for the rest of the evening, leaving the officers of his battalion to complain about their incompetent leader securely and without restraint behind the parked convoy, each man secretly fantasizing about replacing the Lieutenant Colonel.

Without oversight, the soldiers began to destroy what was left of the settlement, pillaging valuables to complement their miniscule wages, gathering food, and subjecting to the remaining beasts of burden and civilians in hiding to the tortures reserved in fantasy for their hated officers, who had whipped, verbally abused, beaten, and even killed those beneath them for years with impunity. Ingolls filled his small sack quickly and modestly before joining Strotsky, who had abstained from the plunder altogether. Their companions, however, wreaked havoc and destruction for as long as they were permitted before returning to the convoy with full packs and swelling egos at being “officers” for half a day, having lorded over the town as they had been lorded over by their superiors.

Lieutenant Colonel Peterson finally reappeared with his uniform ruffled and lightly spattered in someone else’s blood. The none-the-less cheerful Lieutenant Colonel ordered his soldiers to board their trucks. The men complied and drove home in high spirits. They sang marching songs, traded captured loot from their exploits, and ate what remained of their rations. Strotsky played cards with Ingolls and eventually Hubrick before dozing off to sleep. Upon returning to their outpost, the men lined up at the makeshift post office to ship away their “earnings” before the next inspection, during which they would be held accountable for any remaining contraband. Its free time spent, the battalion returned to the oversight of its officers, who directed the now weary soldiers to return to their barracks, undress, and sleep. The men obeyed, bringing the day to an end. In the meantime, Peterson filled out his report of the day’s activities, noting that nothing valuable had been recovered from the town.

Categories:

The Liquidation

October 2, 2017

0

Donate to Sword & Shield

$180

$1000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of University High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.