By TEAGAN SO AND SABRINA HUANG

Staff Writer and News Copy Editor

It was any person’s worst nightmare.

Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher Yu Darvish watched as the baseball soared over his head. He shut his eyes as he saw the ball disappear in the crowds of Astros fans maniacally waving their hands. It was the second inning of the third game in the World Series and millions of people across the nation were watching.

Houston Astros player Yuli Gurriel ran as fast as he could. He circled the diamond as his fellow teammates shouted his name and rushed to pat his back.

The Astros were now in the lead.

Maybe it was the excitement or maybe it was the adrenaline coursing through Gurriel’s veins. He reached up and pulled at the corners of eyes and uttered the word “chinito” as the camera swirled over to him. Millions of people were watching, unable to look away.

Acts like these are not unusual in America. It seems like our American culture, no matter how hard we try, is reluctant to give up feelings of racism and prejudice, whether they be blatant or subtle.

Asian Americans, who currently comprise the third largest racial minority group situated in the U.S., have faced a complex and confusing road regarding their cultural identity. The first Asians immigrated to the United States in the middle of the 19th century as Westward expansion and industrial development swept the country. Like other immigrant groups, Asians (mostly Chinese and Japanese immigrants at first) were in search of a new life across the Pacific Ocean. The group steadily grew throughout the rest of the 19th and 20th centuries despite restrictions on immigration and racially-discriminatory practices. The 1944 Supreme court case of Korematsu v U.S. explored the definition of what it meant to be Japanese-American in WWII-era American society. The holding, adjudicated in the midst of the despicable and slightly ironic conception of Japanese internment camps, ruled that Asian Americans were not Americans; they were immigrants.

The pan-Asian American movement officially started in the 1960s with the establishment of the Asian American Political Alliance (AAPA) at University of California Berkeley and Los Angeles. It wasn’t until the gruesome murder of Detroit teenager Vincent Chin that the movement officially took ground.

Images of Gurriel pulling on the corners of his eyes flooded news stations. In an interview with ESPN after the game, Gurriel admitted that the word “chinito,” which is a derogatory Cuban term for Japanese citizens, was “disrespectful.”

“I did not mean it to be offensive at any point,” Gurriel said in his apology. “Quite the opposite. I have always had a lot of respect [for Japanese people]. … I’ve never had anything against Darvish. For me, he’s always been one of the best pitchers. I never had any luck against him. If I offended him, I apologize. It was not my intention.”

The next day he was suspended for the first five games of the next season without pay.

After racially mocking someone on live television, Gurriel was not prohibited from playing in the World Series; instead, he was allowed to bask in cheers, fame and glory.

Identity is an abstract, intangible concept that eludes understanding. According to the Merriam Webster Dictionary, identity is defined as “the distinguishing character or personality of an individual.” Identity for many, however, is more complicated than eight words.

“People are layers so you have multiple identities,” science teacher Ms. Jennifer Bartlau said. “Nobody has a single identity. You have [multiple] layers [to who you are].”

Identity is not something that can be defined in binary terms. It is a weight scale that can shift with the slightest change.

“You continue to grow and you continue to get comfortable with yourself,” Bartlau said. “You’re constantly being shaped by your experiences and who you are is essentially how you respond to your experiences, not necessarily what comes at you.”

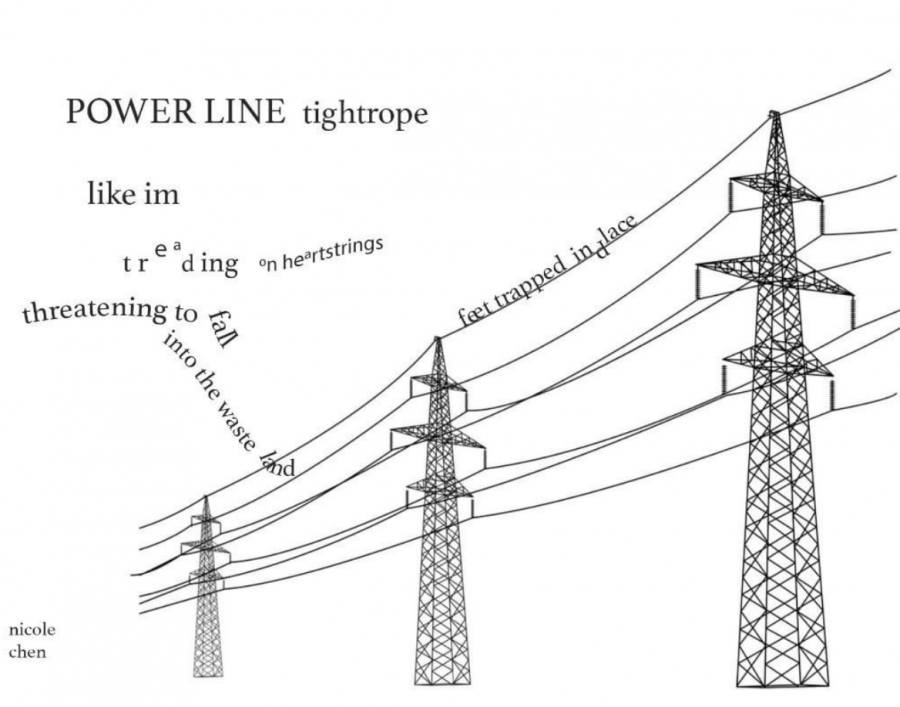

For those who move to America at an older age, finding the right balance between American culture and their native Asian culture is challenging. Moving to America can not only mean leaving behind your family and friends, it can also mean learning a new language, customs, and ideals. It can be difficult to tread the fine line between completely following one culture and creating a blend that celebrates both of the two cultures.

Most students of Asian descent at UHS are born in America, but they still face the same struggles with establishing their cultural identity. Strong influences from both the American society and an Asian family during childhood can often lead to internal conflicts while growing up.

“There were definitely moments when I felt like I didn’t know which [culture] I belonged to, and tried to skate over my Korean heritage in favor of assimilating to American culture, but that didn’t feel right,” a senior, Isabelle Lee, reflects. “Often, I felt that by trying to fit into both cultures, I didn’t belong to either. I’ve felt shamed and pressured to assimilate to American culture before, but I now know better and take pride in being Korean.”

Unfortunately, Asian-Americans are no stranger to the obstacles such as racism and discrimination. Before she was a math teacher at UHS, Ms. Stephanie Chang was a teenager who had moved to America from Taiwan in the 1980s.

“When I first learned English, I had to listen to you, translate into Chinese in my head and answer in Chinese in my head and then translate that answer into English and speak out,” Chang said.

At this time, Chang was a fast-food worker at a Chinese restaurant in Westwood. Her English was not as fluent and she was, in her own words, “slower” than other people. After experiencing this delay in understanding, one customer said “Get back to your country. Don’t come here if you can’t speak the language.”

“I was trying to process what he said,” Chang said. “And I thought people were always joking but I’ve actually had somebody say to my face, that I should go back to my country. At the time, because I was so new to the country, and I was so young and I was so slow….I didn’t know how to react,” Chang described.

“And I just let him say that to my face, and he took off.”

Though at the time she didn’t show any emotions, Chang was angry.

“Why would he say that to me? I do the same thing you do: I pay taxes [and] I do more than you do. [But] I was sad too. Why would somebody say that to me?”

“I was volunteering at a children’s place and a mom came up to me and told me to stop playing with her daughter and that I should call over a white volunteer to play instead,” said one anonymous student.

“During elementary school, there were always jokes about how Asians have ‘small eyes.’ There was even a song about it too,” recalled another student.

Amy Wong, a junior, has also experienced discrimination throughout her life.

“I’m Chinese. I’m American, too. The two aren’t mutually exclusive,” she states. “By blood, I’m Chinese, but by birth, I’m American.”

Most discrimination at UHS happens unconsciously, but the most prevalent form exists through racial stereotypes. Every ethnicity is victim to a slew of prejudiced opinions that not only influence the way people see each other, but also impact the way they hold ourselves to a certain standard. In a poll of 74 students, 67.6% reported that they feel pressured or influenced by such stereotypes.

“I can definitely say that the degree of growing Asian stereotypes and simple jokes about Asians being expected to have a tiger mom and be naturally intelligent has become ludicrous.” says senior Jihee Yoon. “I believe the expectations to perform well in school and different parenting styles depend on every family and shouldn’t be categorized as a race thing.”

At UHS, clubs such as Korean Culture Club and Chinese Culture Club provide an opportunity to immerse oneself in learning about a foreign culture.

“In Korean Club we try to showcase different cultural things that Koreans do.” says Serena Huang, secretary of KCC. “Sometimes we have meetings where we do Korean games or we just play Kpop. We also show history presentations.”

“The Chinese Culture Club’s purpose is to show the different side of Chinese culture beyond the stereotypical,” explains Desiree Chong, one of the presidents of CCC. “Our goal is to spread awareness of Chinese culture to broaden everyone’s views….We want to show that there’s a lot of different cultures that we should respect and be aware about.”

When asked about the biggest cultural difference she’s noticed since moving here from Japan, Junior Alisa Huang replied, “America really loves uniqueness…Where I came from was more close minded. I was educated only to do the things I was told…But America respects individuality.”

This uniqueness and individuality is something that we should all treasure rather than disregard as barriers that divide us from our those who are different.

Our differences are what makes us who we are and we must all accept that the things which seem to separate us from others are in reality the things which bring us closer together with one another.

Everyone is beautiful in their own way.

“We have to respect that society is so much better to have as many different ideas as possible. The more different the better in the end,” Bartlau said. “Being unique is good.”

Even for people who aren’t Asian American, like Bartlau, the struggle to find a balance between two identities is challenging.

For her, this struggle, though not a conscious or tangible entity, exists subconsciously.

“I have an oma (grandma) and opa (grandpa) and they’re from Germany and they moved to the United States in the early 50s,” Bartlau said. “So my dad was the first person born in the United States on that side of the family so when he was younger, when he was in first grade he was discriminated against [for] having come from essentially Nazi Germany at the time.”

Her grandparents strongly felt it necessary to conform to the “American culture” they found present in the country at the time. This included speaking only English and essentially sacrificing most German cultural traditions and practices.

“Literally my oma would open up books and make my aunt [and father] do all English [when they were young]. They even stopped speaking English with them,” Bartlau recalls. “[They had the mentality of] ‘We’re in America now. We’re speaking English now.’”

As a result, her father lost most of the knowledge of German language and culture that his parents carried with them to America when they immigrated.

“I think it’s really sad that my dad has a second-grade level German vocabulary because his parents felt like it was so necessary to conform,” Bartlau said. “I think that’s sad [and] I wish I could speak German. I think that it is necessary and I wish my dad would have [retained more of his cultural heritage].”

Part of establishing an identity is synthesizing different cultures into a balanced whole. For each person, the journey of finding this balance can be difficult and long, but in the end, it is this journey that enables you to discover who you are.

“I think everyone should continually search for their true selves and continue to be as true as they can to that regardless but that’s harder and easier said than done,” Bartlau said. “Holding on tight to things you really enjoy is one of the best things you can do.”