By LISA SHEN

Staff Writer

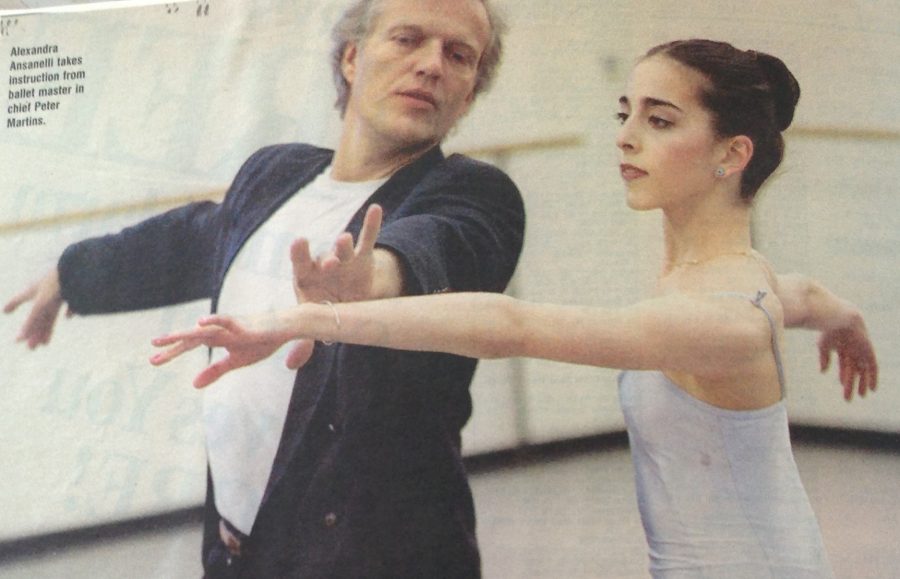

Over a year ago, Peter Martins, a prominent figure in the ballet community, was forced out as artistic director of the New York City Ballet, a position which he had held for the past 35 years. Due to credible allegations of sexual harassment, Martins was outed as part of a broader MeToo movement within the entertainment industry. However, as is the case with many other prominent figures who have been held accountable for their actions when it comes to sexual harassment, Martins’s career never really took a substantial hit. After the fallout settled, he was quickly rehired, this time by the world-renowned Mariinsky ballet, in a move that demonstrates the priorities of ballet as an institution. From its inception, ballet has always been an institution based around a culture of sexism and protecting those in the community that abuse their position of power. In this context, examples such as Martins are not the exception, but the rule.

Ballet’s deep-rooted sexism started from the very beginning and has continued throughout history. Ballet originated in the Italian Renaissance courts in the fifteenth century. Nobles learned the steps and danced during festivals. When Catherine De Medici married King Henry II of France, she brought ballet over to the French courts. Ballet flourished in France under King Louis XIV, nicknamed the Sun King after his performance in “Ballet de la nuit.” It turned from the nobility’s pastime into an actual career, with the King laying out written rules for ballet, the first to ever do so. Ballet was very different from what we know today due to the constraints in clothing and the idea that ballet was just an accessory to the art of Opera. French ballet master, Jean Georges Noverre, went against the idea and introduced the idea of Narrative Ballets, a chance for ballets to be performed on their own.

In all of these story ballets, women are often seen as objects, or a representation of the ideal woman; fragile and delicate, waiting for the men to notice her. The women in these stories are celebrated for their beauty, and a blind willingness to do anything in the name of love. In the story, Giselle dies and become a willi, the ghost of a young virgin girl who has died of a broken heart. Despite having been betrayed, she chose to save Albrecht from the other willis in the end. In Swan Lake, the White Swan Odette can only break her curse with a man’s love, similar to Sleeping Beauty, in which Aurora needs a man to wake her from a hundred-year slumber.

The stories don’t allow for the female roles to have any personality or growth. It creates one-dimensional characters and archetypes that men believe women should follow. Examples include the Sugar Plum Fairy and the Lilac Fairy, guiding the storyline but remaining the same throughout.

After the era of Romantic Ballet, choreographers such as Sergei Diaghilev and Michael Fokine began to steer away from the classical story ballets. Balanchine created a new era with neoclassical or plotless ballets. Women’s role in these new creations have become more full and developed. Although problems still exist, most are generally heading toward a better direction. New ballets by Christopher Wheeldon, Alexei Ratmatsky, Justin Peck among others have created dances with more equitable plotlines.

However, sexism remains as a prevalent issue in ballet as we turn our focus away from the stage.

In an artform that seems to represent females, the number of male artistic directors and choreographers is far larger than that of female leaders. This unequal dynamic, although not the ultimate cause of sexism, is certainly a contributor. To understand this, we must examine how ballet dancers are chosen. Ballet dancers often start at a very young age, at three or four. Those who stay and preserve usually go to professional schools affiliated with companies. This starts a rigorous process that continues for much of their lives. After staying in a professional school, they audition and hopefully get chosen by artistic directors. The selection process does not end when they get into a company, as choreographers are often brought in and they get to decide who will be cast in their pieces.

Through recent news, it was discovered that men in powerful positions often use them to their advantage, starting from these ballet schools. In 2018, Bruce Monk, a teacher at the Royal Winnipeg Ballet School was sued by more than sixty students for sexual misconduct over a period of thirty-one years, from 1984 to 2015. Ballet students often live in an insulated environment, with teachers acting as their authority figures. Ballet historically allows little to no input from the students. This means that it is often hard for students to see what behaviors are normal and what behaviors are overstepping the boundaries.

In addition to their reputation, dancers have other concerns on the line. They are concerned about losing roles or even losing their job if they choose to speak up. Ballet, for many dancers, is their livelihood, and has been their life-long dream and passion. If these dancers choose to speak up, they may give up their chance to dance professionally.

Changes and improvements have been made for the future of equality in Ballet. While it seems that we are heading in the right direction, more changes need to be made, starting from the classroom.

Behind the Curtain: an Examination of Ballet

October 7, 2019

0

Donate to Sword & Shield

$180

$1000

Contributed

Our Goal

Your donation will support the student journalists of University High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover