“Dune” Review

December 8, 2021

A friend of the late Roger Ebert, when it was the latter’s job to review the original “Dune” movie in 1984, described the film as “dreamlike.” His advice to Ebert was that “if you give up trying to understand it, and just sit back and let it wash around in your mind, it’s not bad.” While the original “Dune” movie was critically panned and the new one is superior in all attributes, the advice of Ebert’s friend rings true. “Dune” is a great movie – if you accept that you won’t understand everything.

Coming from famous Canadian filmmaker Denis Villeneuve, who also directed “Arrival” and “Blade Runner 2049,” 2021’s “Dune” is an adaptation of Frank Herbert’s 1965 novel of the same name. The movie is a gargantuan effort—it clocks in at a whopping two hours and 36 minutes, and Villeneuve clearly poured his heart into honoring Herbert’s novel on the big screen. However, this lends itself to a drawback: “Dune” is clearly made only for those who have read the book. Despite the expository nature of multiple segments, it was still a confusing experience. I don’t say this as a criticism against the movie; I still enjoyed it immensely, but anybody interested in watching it should be warned.

“Dune” is the tale of Paul, whose father is assigned by the Padishah of the Universe (Herbert was an extreme Islamophile who commonly worked Arabic, Turkish, and Farsi phrases into his work) to secure the desert planet of Arrakis, the only source of “the spice,” a drug-like resource that powers space travel. Arrakis is populated by the Fremen (a non-subtle portmanteau of the words “Free Men”), ambiguously Muslim natives of the planet who are known as skilled warriors. The actual story of the film feels somewhat lacking however, and the fact that it’s meant to be a two-parter is really felt. It’s not bad by any means; however, much of the movie seems like it’s building up to a climax that never comes: the second part. The story of “Dune” is by and large about Paul’s “jihad,” or as it is called in the movie, his “holy war;” however, this never actually appears in the film, except in premonitions. Ironically, despite the film’s massive runtime, one comes out of it wanting more.

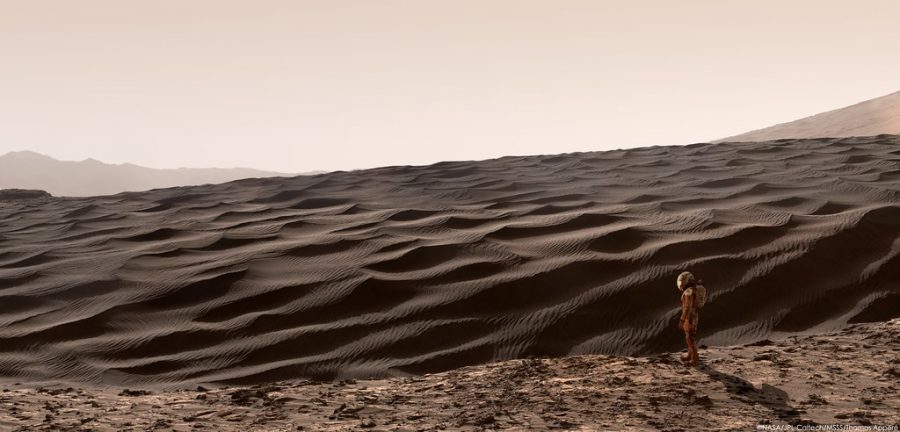

No discussion of “Dune” is perhaps complete without the mention of its most identifiable symbol: sandworms. Massive hostile worm-like creatures, “Dune’s” sandworms are rendered masterfully in Villeneuve’s film. Despite only appearing for about two minutes of runtime, the sandworms may well be the highlight of the experience visually, presented as towering, primordial beings that are built up to and shown perfectly. In general, the visuals of the film are it’s strongest suit, with multiple scenes leaving me in awe of their scale and beauty. The cinematography is brilliant too and at one point a scene legitimately managed to take my breath away. The passion put into the visuals of the film is clear, and has paid off tremendously.

The actors perform well in their roles; however, I feel that there are miscastings littering the film. Paul, at the start of the story, is meant to be fifteen, but his actor Timothée Chalamet, who is a whole ten years older than his character, makes Paul look more like a brooding college student than a young prince. Likewise, despite Herbert’s deep passion for Islamic cultures, critics have noted a lack of Middle Eastern actors filling roles. Generally, the film pulls back from some of Herbert’s more obvious Islamic influences. The concept of “jihad,” a central theme of the novels, was changed to the comfortably Christian “crusade” in the trailer before becoming the blanket “holy war” as a result of backlash.

“Dune” is about a lot of big ideas: war, colonialism, power, the myth of the hero, nature, god-emperors and Zen Buddhism, among others, culminating in such a varied resume of ideas that many only connect them by the fact that they are big ideas. Herbert aimed to tell a tale about the world in his books, not just about huge worms and secret societies. The movie aesthetically lives up to Herbert’s vision and goes beyond, however feels incomplete in what lies beneath. The movie is a brilliant experience, and visually, the kind of stuff that theaters are made for; however, the plot is demanding and once you understand it you demand more of it. It’s beginning a run in IMAX theaters starting December 3rd, which is, I believe, the perfect opportunity to watch it. However, when doing so, it is best to follow the advice of Ebert’s friend. If you do so, you’ll have an intriguing, visually stunning, albeit slightly confusing two hours of watching experience.